A history of the term “Indian”

How a mistake led to misrepresentation.

December 30, 2018

When Christopher Columbus reached the Americas, he believed that he was in the Indian Ocean. He was, in fact, trying to find a westward route to Asia and, at this time, he and those he was with called most everyone from that region of the world ‘Indian.’

Instead of finding Asia, Columbus actually found what was thought to be an area untouched by humans. This area, which had actually been “discovered” previously by Leif Eriksson, was home to a multitude of indigenous people.

This misunderstanding led to a name mixup that is still influencing the United States today. Were it not for Columbus’s mistake and its legacy, indigenous people would not be called Indian. The broadly accepted term is no longer ‘Indian’ but ‘Native American,’ yet there are still many other names people use when referring to indigenous persons.

The United States Census Bureau files the group of indigenous people in the U.S. under the terms “American Indian” and “Alaska Native,” or “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.”

Instead of using one of these names, people might choose to identify with their tribe. For example, people who belong to the Navajo tribe might use the term “Dineh,” which translates to “The People.”

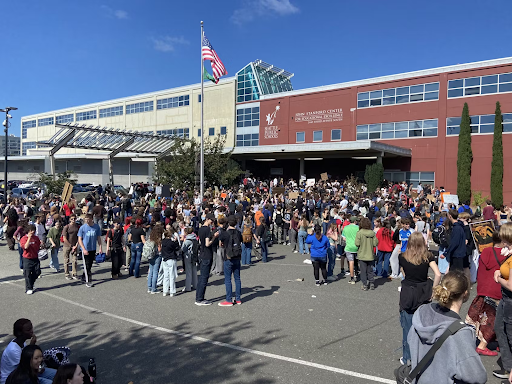

Here at BHS, multiple students and teachers have said that they regularly use the words “Native American” when describing indigenous people. The most common name that they have heard used in place of Native American is, not surprisingly, “Indian.”

In the entire Northshore School District, less than one percent of students identify as “American Indian” and “Alaska Native,” whereas in all of Washington State, that number increases to about 1.9% of the population. Compared to the rest of the country, Washington consistently falls in the top ten states most populated with Native Americans.

Columbus and his crew thought the Americas was India, leading them to call the Native Americans ‘Indian.’ Centuries later, we’re still living with this misidentification.